You can access a free copy of their journal article here .

Internet Editor’s Note: Drs. Leichsenring and Salzer recently published an article titled “A meta-analysis of psychodynamic psychotherapy outcomes: Evaluating the effects of research-specific procedures” in Psychotherapy.

Overcoming the Narcissism of Small Differences

Anxiety disorders represent a significant public health concern due to their prevalence, associated impairment and economic impact (Gustavsson et al., 2011; Wittchen et al., 2011). Various empirically supported methods of psychodynamic therapy for the treatment of anxiety disorders are available (a review was recently given by Leichsenring, Klein, and Salzer, 2014).

In clinical practice, you may come across a patient diagnosed with both a social anxiety disorder and a comorbid panic disorder. So what treatment approach to apply? Malan’s (1979) brief psychodynamic therapy supported by Knijnik et al. (2004) and Bögels et al. (2014)? Or the concept by Leichsenring, Beutel, and Leibing (2007) based on Luborsky´s (1984) supportive expressive therapy? Or should we apply the concept of panic-focused psychodynamic therapy by Busch et al. (2012) which has proven to be efficacious in panic disorder (Milrod et al., 2007) and has been extended to other anxiety disorders? In the training of psychotherapists, we are confronted with a similar problem.

Is it necessary that candidates learn to apply all empirically supported treatment concepts for the different mental disorders?

Moving Towards Transdiagnostic and Modular Treatments

To address these problems, psychotherapy research is moving its focus from single-disorder approaches towards transdiagnostic and modular treatments (e.g. Barlow, Allen & Choate, 2004; McHugh, Murray & Barlow, 2009). The rationale for transdiagnostic treatments focuses on similarities among disorders, particularly in a similar class of diagnoses (e.g., anxiety disorders) including high rates of comorbidity (e.g., Kessler et al., 2005) and improvements in comorbid conditions when treating a principal disorder (e.g. Barlow, Allen & Choate, 2004; McHugh, Murray & Barlow, 2009; Norton & Phillip, 2008).

Empirical Support for Transdiagnostic Treatment

Psychodynamic therapy has proven to be efficacious in anxiety disorders (Keefe et al., 2014; Leichsenring, Klein & Salzer, 2014). However, a unified and transdiagnostic protocol that integrates principles of empirically supported treatments has not existed so far.

The available evidence for psychodynamic therapy in specific mental disorders comes from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that used different treatment concepts (Leichsenring, Klein & Salzer, 2014). This implies that the evidence for psychodynamic therapy is “scattered” between the different forms of psychodynamic therapy, not only for anxiety disorders, but for other mental disorders as well (Leichsenring, Klein & Salzer, 2014).

Interestingly, it was for this very reason that psychodynamic therapy was judged as only “possibly efficacious” (Chambless and Hollon, 1998) – to be judged as “efficacious” at least two RCTs are required in which the same treatment is effectively applied to the same mental disorder (Chambless & Hollon, 1998).

Overlapping Characteristics of Psychodynamic Therapies

Psychodynamic therapy shows several characteristics that facilitate the development of a unified psychodynamic protocol:

(1) Psychodynamic psychotherapy is transdiagnostic in origin

Psychodynamic psychotherapy is traditionally not tailored to single mental disorders or specific symptoms. It focuses on core underlying processes of disorders; that is, on unresolved conflicts or structural deficits defined as impairments of ego-functions (e.g., affect regulation, mentalization, internalized object relations or insecure attachment). Thus, psychodynamic therapy is transdiagnostic in origin.

(2) Psychodynamic treatment manuals have a modular format

Treatment manuals for psychodynamic therapy typically have a modular format allowing for a flexible use. This is especially true for the available manual-guided psychodynamic treatments for anxiety disorders (e.g., Busch et al., 2012; P. Crits-Christoph et al., 1995; Leichsenring, Beutel & Leibing, 2007). By the modular format, both the course of treatment and individual differences between patients (e.g., patient motivation, severity of pathology) can be taken into account. The modular format also allows the “dose” of each treatment element to be adapted to each individual patient’s needs.

(3) Manual-guided methods of psychodynamic therapy for anxiety disorders have core treatment principles in common

The available evidence-based forms of psychodynamic therapy for anxiety disorders have several core principles in common that outweigh the differences between the treatments. This applies to the treatment of panic disorder with and without agoraphobia (Busch et al., 2012; Wiborg & Dahl, 1996), generalized anxiety disorder (P Crits-Christoph et al., 1995)and social anxiety disorder (Bögels et al., 2014; Knijnik et al., 2004; Leichsenring, Beutel & Leibing, 2007).

Developing a Unified Protocol for the Psychodynamic Treatment of Anxiety Disorders

We are here proposing a unified psychodynamic protocol for anxiety disorders (UPP-ANXIETY) that integrates the treatment principles of those methods of psychodynamic therapy that have proven to be efficacious in anxiety disorders.

The term “unified” refers to several aspects that are integrated:

(a) different treatment principles used by different empirically supported methods of psychodynamic therapy in

(b) various types of anxiety disorders were integrated within a unified protocol for

(c) a diagnostic class of anxiety disorders, thus

(d) also contributing to “unifying” the evidence of psychodynamic therapy and enhancing the evidence-based status of psychodynamic therapy .

In addition, this protocol is transdiagnostic implying that is it is applicable to various forms of anxiety disorders and related disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorders, avoidant personality disorder). Based on supportive-expressive therapy (Luborsky, 1984), the UPP-ANXIETY represents an integrated form of psychodynamic therapy that allows for a flexible use of empirically supported treatment principles.

The 9 treatment principles (modules) of UPP-ANXIETY:

- socializing the patient for psychotherapy

- motivating and setting treatment goals

- establishing a secure helping alliance

- identifying the core conflict underlying anxiety

- focusing on the warded-off wish/affect

- modifying underlying internalized object relations

- changing underlying defences and avoidance

- modifying underlying response of self;

- termination and relapse prevention.

Summary and Benefits

The benefits of a unified and transdiagnostic protocol for the psychodynamic treatment of anxiety disorders include:

- Integration of the most effective treatment principles of empirically supported psychodynamic treatments for anxiety disorders which can be expected to further improve the efficacy of psychodynamic therapy

- Enhancement of the evidence-based status of psychodynamic therapy by aggregating the evidence

- Facilitation of both training in psychodynamic therapy and transfer of research to clinical practice, thereby significantly impacting the health care system

There are now several types of psychotherapy that have been shown to be effective in treating social anxiety disorder. One of these approaches is psychodynamic therapy.

For the longest time, it was not included in the standard treatment recommendations for socially phobic individuals, as it was lacking sufficient evidence for its effectiveness. However, this has changed throughout the last decade.

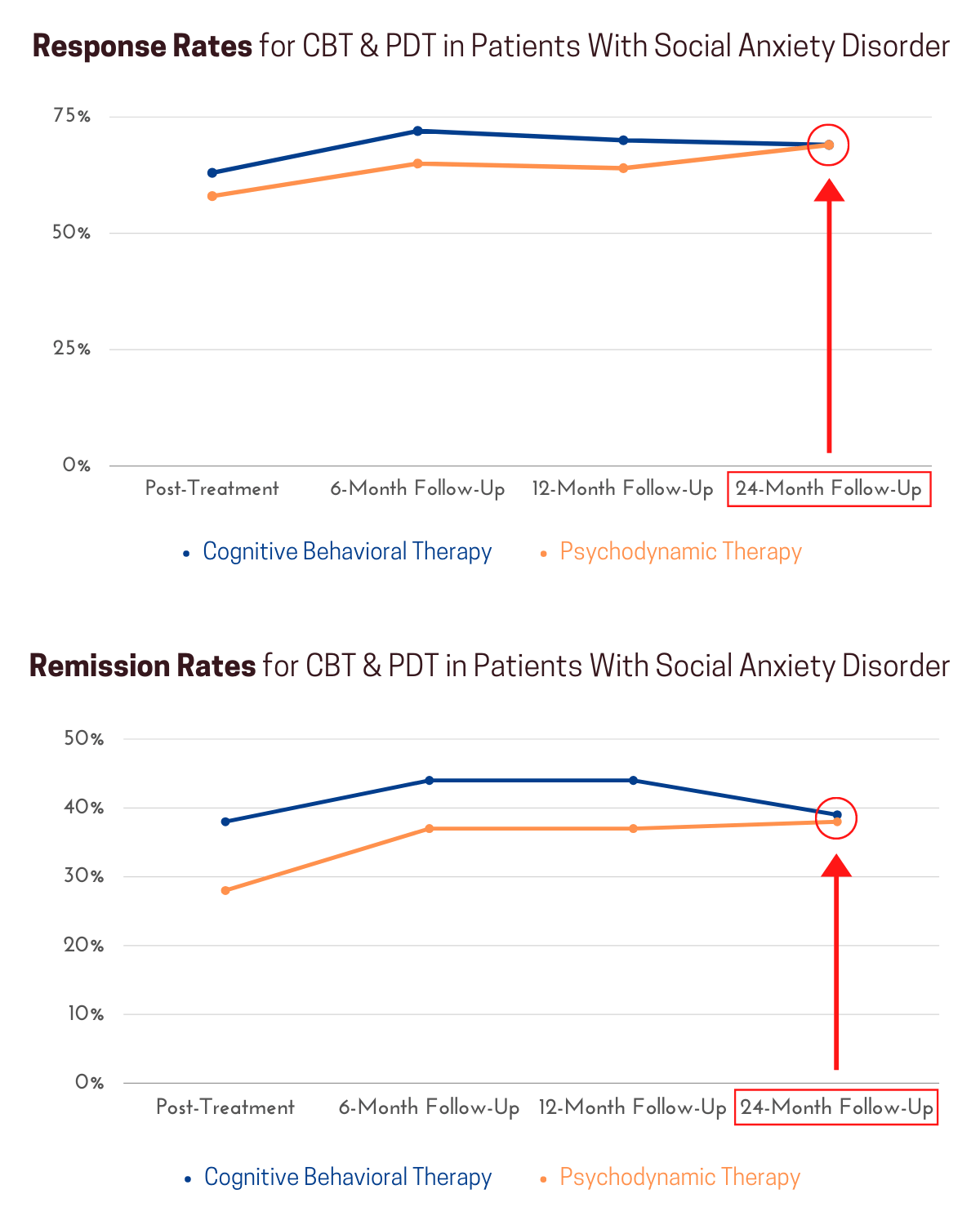

Psychodynamic therapy (PDT) has been shown to be as effective as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in the treatment of social anxiety disorder (SAD). While CBT can yield slightly better results in the short-term, PDT is just as effective on the long run and represents a valid treatment option.

Have a look at the following statistics from a long-term outcome study carried out by Leichsenring and colleagues (2014). You will see that when comparing their effects 2 years after the treatment intervention, CBT and PDT had led to almost identical results.

The response rate refers to the percentage of patients who experienced a significant decrease in social anxiety because of treatment. The remission rate indicates the percentage of patients who overcame their social anxiety disorder altogether.

Many socially anxious people do not respond to the standard treatment recommendation of CBT and many are repelled by the idea of gradually exposing themselves to the situations they fear.

This not only causes many people to prematurely drop out of the treatment process, but many people do not even start it in the first place.

PDT is a great option for these individuals, as well as for those who look for a more in-depth understanding of their problem.

Here, we will have a closer look on this approach and break down how it explains and treats social anxiety.

What is Psychodynamic Therapy?

Psychodynamic therapy analyzes the unique way in which a person relates to others. Based on psychoanalytic theory, it argues that interpersonal relationships are the driving force of the human psyche. Psychological insight in these mostly unconscious relational patterns can lead to symptomatic relief.

Given its psychoanalytic roots, PDT places great importance on the unconscious, the therapeutic relationship, and an analytic attitude. Therefore, it is often also referred to as relational psychoanalysis.

With its focus on the patient’s interpersonal relationships, treatment primarily attempts to analyze the following aspects:

- The patient’s main bonds (Their most important relationships)

- The relational environment (With whom does the patient relate? How significant are these relationships to them?)

- Intersubjectivity (Emerges when two people interact with each other; it has conscious and unconscious components)

- Object relations (In PDT, “object” refers to a person that has affective meaning to the patient)

Let’s have a closer look at why the patient’s central bonds are so important.

The Importance of the Bond in Psychodynamic Treatment

When we experience problems with the people that are most important to us, psychodynamic therapy speaks of a relational (also: dynamic) conflict. If the dynamic conflict is significant and remains unconscious or unresolved, symptoms may emerge as a result.

According to psychodynamic theory, the bond is the raw material of mental life and we are the result of passing through this relationship.

In other words, our most important relationships provide the matter we are built of. Without them, we would not exist. We only exist in relation to others.

Therefore, the patient’s relationships lie at the core of PDT.

Relational Theory & Social Anxiety Disorder

There are many important contributors to psychodynamic theory. However, the following three authors are most important when it comes to the development of social anxiety.

John Bowlby (British psychiatrist & psychoanalyst)

Bowlby coined the term attachment style. He believed that the mother-child relationship (or other primary caregiver) determines our relational patterns throughout the rest of our lives.

Do we seek close bonds or do we hold others at distance? Are we driven by fear of being abandoned or do we trust others?

If this crucial, first relationship to our mother is not safe and secure, we may develop an insecure attachment style, which has been linked to many psychological problems, such as social anxiety.

Donald Winnicott (British pediatrician & psychoanalyst)

On a similar note, Winnicott believed that the mother (or other primary caregiver) plays a decisive role for the psychological development of her child. He proposed the concept of the good enough mother.

He argued that the mother does not need to be perfect, as long as she meets the child’s needs in a good enough way. If she fails to do so, her child may feel that their true self is unacceptable to her, leading to the development of a false self.

This is seen as a psychological defense mechanism to protect the child’s true self and can lead to social anxiety.

Melanie Klein (Austrian psychoanalyst)

Klein argued that one of the main struggles we face as children is the realization that we are separated from our mother (or other primary caregiver). At this point, the child understands that mother (object) and child (subject) are not the same entity.

When this happens, the child becomes aware that both, feelings of love and also hate, exist in relation to the mother. This hate emerges as the child projects their own destructive parts onto her. This gives rise to fear of being punished (Klein calls this the “paranoid position”).

When the child succeeds in acknowledging that the mother has good and bad sides, they experience feelings of guilt and want to repair the damage done (which they caused in their imagination). This is called the “depressive position”.

If this process of (imagined) reparation is not successful, social anxiety can develop because the objects are experienced as hostile and persecuting.

Among psychodynamic theorists, there is a strong consensus about the importance of the mother-child relationship, especially during early childhood.

The following is a list of childhood experiences commonly reported by socially anxious individuals (Baeza, 2007):

- The feeling that love, approval, or even attention had to be achieved (instead of being provided unconditionally).

- The relationships to the primary caregiver(s) were insecure and unpredictable (instead of safe and secure).

- General lack of emotional support and growing up in a critical family environment (instead of supportive caregivers).

- Feeling abandoned at crucial moments during childhood (which often leads to fear of getting attached to others).

As you can see, the quality of a child’s first important bond(s) determines the psychological foundations for the rest of their life.

However, this does not mean this predisposing framework cannot be modified at a later point. That’s precisely where psychodynamic therapy steps in.

How Does Psychodynamic Therapy Treat Social Anxiety?

Similarly to psychoanalysis, psychodynamic therapy encourages the patient to put as many of their psychological experiences into words as possible.

Treatment is non-instructive and believes that it is the patient themselves, not the therapist, who possesses the knowledge that can lead to a cure.

However, this knowledge is mostly unconscious. The therapist’s job is to help the patient access this hidden knowledge and make sense of their experience.

A main tool to do this is the therapeutic relationship. As patient and therapist work together, their mutual relationship works as a driving force for change.

During the treatment process, patient and therapist try to discover the relational experiences that caused the social anxiety to emerge.

At the same time, they pay close attention to the patient’s current relationships and see if they transform along way.

In a sense, the therapeutic relationship has the potential to provide a corrective experience for the patient, meeting whatever emotional need that may surface during the course of treatment.

Contrarily to symptom-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, traditional PDT has an important ascetic component to it.

This means that PDT does not seek a cure to specific psychological problems per se. Instead, it attempts to cultivate self-knowledge, which can lead to self-transforming experiences.

However, given its alleviating effects, it is now often used as a means of symptom reduction. There are several brief interventions (10-36 sessions) that have been shown to reduce social anxiety quite reliably (Bögels, Wijts, Oort, & Sallaerts; Johansson et al., 2017; Leichsenring et al., 2013).

Among the objective changes that can often be observed throughout the treatment process are:

- Improved communication skills

- Better conflict management

- Enhanced assertiveness

- Decreased social isolation

However, psychodynamic treatment is especially interested in the subjective changes the patient experiences.

Given their nature, they cannot be generalized. However, noteworthy are the significant reductions in social anxiety experienced by most patients included in these trials.

An important component of PDT is the analytic view the patient is likely to develop while passing through the therapeutic process. By analyzing all their important relationships in detail, this attitude is likely to accompany the patient even after they finish treatment.

The process of recognizing and solving interpersonal tensions and conflicts that are experienced in the therapeutic relationship can then be applied to the patient’s significant relationships outside of the therapeutic setting. Therefore, PDT tends to have substantial long-term effects.

Let’s have a look at one of the many concepts that are often applied in treatment.

The Core Conflictual Relationship Theme (CCRT)

A concept commonly used by psychodynamic therapists to identify and work on problematic relational patterns is the Core Conflictual Relationship Theme (CCRT; Luborsky, 1984).

It refers to a harmful pattern in the moment of relating to others and it consists of three different elements. A wish from the patient, a response from one or several others, and a response from the patient.

An example of a CCRT for a socially anxious person could look something like this (Gabbard, 1992, as cited in Leichsenring, Beutel, & Leibing, 2007):

“I wish to be affirmed by others (W). However, the others will humiliate me (RO). I feel ashamed and get afraid of being together with others, so I have decided to avoid exposing myself (RS, symptoms of social phobia).”

Despite this being a common example, keep in mind that the CCRT of socially anxious people may differ significantly from the one above.

Important to note is that the CCRT gets activated when a person with SAD perceives external and internal danger.

During treatment, therapist and patient try to identify the patient’s unique CCRT, which is closely linked to the social anxiety symptoms.

Subsequently, this specific relational pattern represents the main topic of interest in the therapeutic process.

If patient and therapist establish a strong therapeutic alliance, they can identify and analyze how the CCRT shows up in the therapeutic setting.

By doing so, the central conflictual relationship theme can be actively changed, which potentially leads to reductions in social anxiety.

Differences to Traditional Psychoanalysis

Given their similarities, many people put psychoanalysis and other psychodynamic approaches into the same box. After all, psychoanalysis is a psychodynamic approach and provides the ground in which other dynamic approaches are rooted.

However, there are some important differences that justify a distinction between the two. Let’s have a quick look at them.

Traditional Psychoanalysis(Other) Psychodynamic ApproachesThe subject’s (client’s/patient’s) drives and impulses are the primary focus.The link between the subject and others is the primary focus.The object (other person) is seen as a needs to an end to satisfy the subject.The subject and object depend on each other, as it is their bond which leads to satisfaction.Relationships are a needs to an end to obtain pleasure.Relationships provide the matter we are built of. We need them to exist.The subject develops as it satisfies its drives and learns how to control them.The subject develops as it relates to others and establishes important bonds.

Is Psychodynamic Therapy the Right Choice for You?

By now, you probably see that PDT is a valid treatment option for those who suffer from social anxiety. However, this does not mean that it is automatically the right choice for you in your specific situation.

Putting it in simple terms: If you are looking for a symptom-focused approach that teaches you specific techniques and can lead to quick results, CBT may be the better option.

With that said, PDT offers a more profound approach and has the potential to address the root cause of your social anxiety (and not just scratch the surface).

(As we aim to provide unbiased information on this website, we want to point out that many CBT therapists believe that our distorted views, irrational thoughts, and maladaptive avoidance behaviors are the root cause of social anxiety. According to this view, CBT addresses the root cause of SAD).

As difficult as it may be to see, anxiety is often the result of interpersonal tensions, conflicts, and difficulties. Identifying them and changing your relational patterns can have a profound, positive impact on your symptoms.

Additionally, as the trials we mentioned above showed, PDT can lead to quick results.

In the end, only you can decide whether or not a psychodynamic approach is right for you. If you suffer from social anxiety, the most important thing is that you start a therapeutic process. Be it PDT, CBT, or any other effective therapy we highlight in our complete treatment guide.

If you are not sure what type of approach an institution or a therapist offer, reach out and ask. Like this, you increase the chances of starting a therapy you will like and stick with.

Conclusions

- Psychodynamic therapy is based on the idea that interpersonal bonds are the matter we are built of.

- There are numerous perspectives which differ slightly. However, there is a general consensus about the importance of the child-mother bond during early childhood and how it predisposes our psychological makeup throughout the rest of our lives.

- Why exactly we suffer from social anxiety is hard to pinpoint and is difficult to generalize. Answering this question for a given person is one of the goals of PDT.

- The basis of psychodynamic treatment is the relationship and communication between the patient and the therapist.

- Treatment seeks to control and learn to live with anxiety. This is achieved by understanding the unique way in which we relate to others.

- Psychodynamic therapy is an effective treatment for social anxiety, especially on the long-term.

- The type of therapy you seek and the therapist you choose have an important influence on whether or not you find it helpful and stick with it. Reach out and ask what type of therapy is offered and do not shy away from changing your therapist if you feel you have a bad fit.

Participate in a Research Study!

If you are affected by social anxiety, you can help researchers and clinicians better understand the condition and improve treatment efficacy by participating in a research study.

To take part, you can click here to open a short, quick survey in a new browser window, or simply fill out the form provided below. Thank you for your participation!

Also, if you suffer from social anxiety and are looking for ways to get better, feel free to sign up for our community newsletter.

By subscribing, you’ll receive valuable information about the condition, its treatment options, and practical advice on how to cope.

Community members are kept up to date on the latest scientific findings, informed about new releases (e.g. our upcoming online course) and receive special discounts.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

By signing up, you will instantly receive a welcome email with our “Social Anxiety Fact Sheet”, “Social Anxiety Treatment Sheet”, and our “Practical Tips Sheet”.

Enter your email address to subscribe

I agree to receive your newsletters and accept the data privacy statement.

You may unsubscribe at any time using the link in our newsletter.

We use Sendinblue as our marketing platform. By Clicking below to submit this form, you acknowledge that the information you provided will be transferred to Sendinblue for processing in accordance with their terms of use

Baeza Velasco, Carolina. (2007). Tratamientos eficaces para el trastorno de ansiedad social. Cuadernos de neuropsicología, 1(2), 127-138. Recuperado em 04 de junho de 2021, de http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-41232007000200004&lng=pt&tlng=es.

Bögels, S. M., Wijts, P., Oort, F. J., & Sallaerts, S. J. (2014). Psychodynamic psychotherapy versus cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder: an efficacy and partial effectiveness trial. Depression and anxiety, 31(5), 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22246

Gabbard G. O. (1992). Psychodynamics of panic disorder and social phobia. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 56(2 Suppl A), A3–A13.

Leichsenring, F., Beutel, M., & Leibing, E. (2007). Psychodynamic psychotherapy for social phobia: a treatment manual based on supportive-expressive therapy. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 71(1), 56–83. https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.2007.71.1.56

Leichsenring, F., Salzer, S., Beutel, M. E., Herpertz, S., Hiller, W., Hoyer, J., Huesing, J., Joraschky, P., Nolting, B., Poehlmann, K., Ritter, V., Stangier, U., Strauss, B., Stuhldreher, N., Tefikow, S., Teismann, T., Willutzki, U., Wiltink, J., & Leibing, E. (2013). Psychodynamic therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in social anxiety disorder: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. The American journal of psychiatry, 170(7), 759–767. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12081125

Leichsenring, F., Salzer, S., Beutel, M. E., Herpertz, S., Hiller, W., Hoyer, J., Huesing, J., Joraschky, P., Nolting, B., Poehlmann, K., Ritter, V., Stangier, U., Strauss, B., Tefikow, S., Teismann, T., Willutzki, U., Wiltink, J., & Leibing, E. (2014). Long-term outcome of psychodynamic therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in social anxiety disorder. The American journal of psychiatry, 171(10), 1074–1082. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111514

Luborsky, L. (1984). Principles of Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy: Manualfor Supportive-Expressive Treatment. New York, Basic Books.

Share & Follow